James McGill

Contents

Background

McGill was born in 1834 at Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, and arrived in Victoria on 11 August 1853. Upon arrival he almost immediately went to Ballarat. Raffaello Carboni called him short and said “what’s up” was his motto.

James McGill died in 1883.

Goldfields Involvement, 1854

McGill made a speech at the dinner for Consul James Tarleton 0n 28 November 1854. Distant shots were heard during the dinner and officials left hurriedly. James McGill rushed in and whispered a password, thought to be the Celtic 'Faugh-a-balagh' meaning 'clear the way. The diners knew the army was on the way.[1]

McGill returned to Ballarat in 1857 and married Eliza Rose Watt Carlington at Ballarat. He was living in Skipton St Ballarat in the 1880s, and died in Victoria in 1883.

McGill was a participant in the Eureka uprising and Commander of the Californian Rifle Brigade, who claimed to have attended Westpoint, [2] under the name of McGillicutty.[3] McGill was appointed second in command because of his military experience and arrived at Eureka with 200 men. He organised the Stockade sentry system. The Californian Rifle Brigade (Independent California Rangers' Revolver Brigade) entered the Eureka Stockade on 02 December 1854, and left the Stockade to intercept Major Nickle’s men. After the battle McGill fled to Creswick wearing women’s clothes furnished by Mrs Sarah Hanmer. The story of his escape was told 50 years later in the pages of the Evening Echo:-

- He was met at Springs by Mrs Hammer [sic] and another, who furnished him with women's attire, in which he travelled by coach to Melbourne on the 5th, passing Sir Robert Nickle and his troops on their way near the Moorabool. By advice of the notorious G.F. Train, then Melbourne agent for the White Star Company's line of ships, Magill, [sic] disguised afresh in man's attire, went on board the Arabian as an officer of the ship. In the meantime Train and other American citizen interposed on behalf of their compatriot, whose youth - he was then about 21 years old - they pleased in bar of grave punishment.

- Train sent to Magill [sic] one day, got him ashore, took him to Sir Charles Hotham's at Toorak, and after a brief interview the Governor, who expressed surprise at Magill's [sic]youth, bowed them on hopefully. Train next informed his client that the government would not interfere to prevent his escape if he left the colony forthwith. Magill, [sic] however, still be the watchful Train's agency, was passed on the health officer's quarters at Port Phillip Heads, where he remained until the acquittal of the State prisoners proclaimed liberty to all the compromised.[4]

McGill wrote to friends at Fiery Creek regarding the whereabouts of Joseph Little, whose whereabouts were unknown after the battle. McGill was present in January 1856 for the discussions involving a monument.

Colt revolvers were percussion cap weapons. Colts in use on the Victorian goldfields in 1854 were the Pocket Colt - a .31 calibre 1849 model; the .36 calibre 1951 model known as the Navey Colt.; and the .44 calibre Walker Colt of 1848. [5]

The colt could misfire and were not very accurate unless at close range.[6]

James McGill carried a Walker Colt. [7]

Post 1854 Experiences

Obituary

- Wednesday Evening - An old identity of Ballarat has just gone to his long home after a chequered and of late years an unfortunate career. He name of James McGill was as familiar as a household word to the diggers of your district in the early days of the goldfields; but it will now perhaps be remembered by very few of the inhabitants of Ballarat of the present era. He arrived from the United States of America with a considerable sum of money - it is said as much as ₤30,000 - in his possession, and shortly afterwards took up his abode at Ballarat, where he made himself actively useful in many ways in connection with his local mining interest. He became much regarded for his strict integrity and excellent social qualities, but as years rolled on he lost all his capital through unsuccessful speculation, and eventually left the district a ruined man. Like too many others of his class, he sought consolation for his misfortune in the “flowing bowl,” and his face gradually got to be as familiar in the hotels of Melbourne as it had once been in the Main road of the Golden city. Recently he had been living at Sandridge, where he died on Sunday last, his end having probably been somewhat accelerated by the habits of “nipping” which had unfortunately taken possession of him.[8]

In the News

- Census. MESSRS. R SCOTT, P. Reade, A. Lessman, J. Stodart, J. H. Magill, and E. Devereux, arc requested to call on thc under- signed immediately, to amend certain census papers, necessary for the payment of their salaries.

- S. IRWIN,

- Enumerator for North Grant Ballarat 5th May, 1857.

- Municipality of Ballarat East.[9]

- OBITUARY - MR R. LESLIE McGILL. Mr R. Leslie McGill, a veteran of Ballarat goldfields, died on April 30 at Inverell, NSW, aged 80. He was the only son of the late Mr James H. McGill, who was one of the miners' leaders at the Eureka Stockade, and of Mrs Rosa McGill, a former principal of Berwick Girls' School, who died in 1920. Mr McGill, who was unmarried, is survived by 2 sisters-Mrs Blanche McGill Ashford (North Brighton) and Mrs Edith McAdam (England). Another sister, Mrs M. G. Neate, of Elsternwick, died in 1939.[10]

- James Herbert McGill, a young Irish-American intelligence officer, who assisted the Ballarat miners in their rebellion, was condemned, after he had escaped in a woman's clothes, as a traitor to their cause. Unwilling to reveal the secret of his duty, he was misjudged except by his intimate friends. Documents in the possession of his daughter, Mrs. Blanche McGill Ashford, of East Malvern, explain why he was not there when the Eureka Stockade fell.

- McGill's wife Rosa Watt McGill tried to clear her husband's name after his death. Writing to her daughter in the United States of his association with the Stockade she said - "This reads as mere romance perhaps but it is true"

- McGlll's correct surname was McGillycuddy, and he belonged to the old Irish family, McGillycuddy of the Reeks which is still extant in the County of Kerry. He was born in the United States when his parents were visiting their Boston estate during a potato famine in Ireland. Later in 1848 his parents and their children settled there and became American citizens.

- A military career was chosen for the McGlllycuddy boys. They attended the West Point training school. When they were considered capable of undertaking serious duties their surname was reduced to McGlll, so that their origin would be less obvious. It was then that James Herbert McGillicuddy (known for the remainder of his life as James Herbert McGill) left in a sailing vessel for Australia on a secret mission.

- Exactly what was his duty has never been disclosed but it is thought that he had to investigate the treatment of Americans who were very numerous on the goldfields. Many of the less successful 'forty-niners' in California had gone to Australia with renewed hopes of finding gold. At the time relations between the Victorian and United States Governments were occasionally strained.

- McGill Reaches Ballarat

- RELATED to the famous Daniel O'Connell and a descendant of early Irish kings the ardent young McGill soon found an outlet for his romantic temperament in the city of tents at Ballarat. He became a competent miner.

- The oppression from which the diggers suffered has been recognised by every commentator on the period. Edward Wilson writing in "The Argus " repeated his demands that the Government should grant them justice. The licence fee of £1 a month which every digger had to pay irrespective of the amount of gold won, was considered a form of taxation without representation, because many had no franchise.

- McGill's youthful passionate idealism received a shock from the treatment of the miners. The minimum fine for having dug without a licence was £5. Half was paid to the informant, with the result that unjust convictions were frequently made on the information of corrupt police. A dishonest magistrate was dismissed eventually for breach of duty. Miners who were digging had to have their licences in their possession and it was the practice of many troopers to call up diggers several times a day from 130ft below the surface. This led to hard words and charges of assault. The payment of the licence fee was harsh enough in itself but corrupt and often cruel administration of the impost stirred discontent into rebellion. Not because he was an agent provocateur, but because of his sympathy with his fellows McGill took up the cause of the miners.

- Spirit of Revolt

- A incident which had nothing to do with the licence system heightened the spirit of revolt in the town. Three men were imprisoned for having burnt down an hotel which was owned by a notorious man who had been freed of a murder charge. After an inquiry the hotelkeeper was convicted and the magistrate who had discharged him was held by a commission to be indirectly responsible for the incendiarism. Although the three men had been in a crowd of 10,000 rioters at the time of the offence an appeal against their conviction was dismissed. A moderate Reform League protested to the Governor (Sir Charles Hotham) without success. Riots resulted and the organisation of the diggers began seriously.

- On November 28 a dinner was given to the American Consul (Mr Tarleton).

- Miners and Government officials were present. In the distance shouting and occasional firing of shots sounded ominously. The officials left hurriedly. McGlll rushed in and whispered the stockade leaders' password. It was a Celtic word Faugh-a-bal-lagh ' meaning clear the way. The diners knew that the army was arriving.

- "I propose the toast of Her Majesty the Queen" said the president of the dinner (Dr Otway). Nobody responded. After a long silence a man stood and replied - "While I and my fellow colonists claim to be and are thoroughly loyal to our sovereign lady the Queen, we do not and will not respect her men-servants, her maid- servants, her oxen nor her ASSES ".

- The pelting of the police with stones and the burning of licences to thwart an inspection were signs of the coming rebellion. Peter Lalor was elected commander of the miners, and a weak stockade of timber and odd pieces of mining material was erected aiound the diggings.

- McGill's Irish enthusiasm for what lie believed to be a just cause and his education fitted him for leadership. The diggers wondered that such a young man should seem experienced in military matters, but they asked few questions and gave him the task of instructing the rebels in rifle drill.

- Before daylight on Sunday, December 3, 1854, 276 soldiers and troopers crept unexpectedly on the stockade, in which there were only about 200 ill-equipped defenders. McGill, like many others, was absent, and his Californian rangers had to fight without their military leader. The stockade fell. Peter Lalor, his arm shattered by a bullet, saw that defeat was imminent. Standing on a log, he shouted to his men "Get away, boys quick as you can, the stockade is taken".

- Meanwhile McGill had received a message to get in touch with the American Consul, for whose safety he was partly responsible. He could not explain his mission to the other leaders, so he left for the ranges, as one historian says, "with some riflemen, ostensibly for the purpose of opposing the troops expected from Melbourne". Later he found that the stockade had been taken in his absence. Nobody had expected the attack by the authorities.

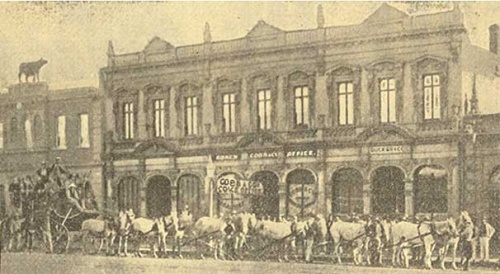

- McGill dressed himself in the clothes of a woman friend and escaped to Geelong in a Cobb's coach. The disguise was successful, and his youthful appearance made him sufficiently attractive for a man to propose marriage to him, but under the protection of Victorian bashfulness he said nothing.

- Suspicion is Aroused

- When he arrived in Melbourne McGill evaded the authorities by hiding in the home of some Americans. An officer of an American vessel, the Arabian, which was in port lent him some clothes and he attempted to conceal himself by living on the ship. When much of the official bitterness towards the stockaders had abated his friends negotiated with the authorities, and he was taken before Sir Charles Hotham. Aged only about 21 years, McGill appeared so young that the stern Governor was easily induced to pardon him. "You are free," said Sir Charles Hotham. "Your youth might have excused a graver offence".

- The pardoning of McGill and his absence from the stockade when the attack occurred aroused the suspicion of all except those who knew him well enough to believe that he was incapable of betrayal. "I charge McGill with treason,' wrote Frederick Vern, a leader of the miners, to Peter Lalor. Lalor was not so quick to make a judgment as Vern, who is described as a boastful extravagant person. Always a friend of McGill Lalor said, "It makes my heart ache when I see how much he has been misrepresented".

- McGill married three years after the rebellion. A rocking-horse was given to one of his children by some of the stockaders who believed in him. It was as large as a Shetland pony according to Mrs Blanche McGill. She remembers that it was named Faugh-a-bal- lagh, after the password which was uttered in such dramatic circumstances. Like many others who had rebelled, McGill became a pioneer of the city of Ballarat, where he was an early member of the Stock Exchange. Suffering from tuberculosis he died in 1883.

- Although the stockade became only a memory, McGill s wife, Rosa Watt McGill, resented the unjust accounts of her husband's activities which were occasionally published. "He had no faculty for conserving his own interests or advantages" she wrote to John Lynch, another famous leader, in 1899. 'Those who could do so and were less deserving, now get undue prominence. And so the difficulty of producing truth in history repeats itself " Lynch replied, expressing agreement with her.

- In her letter Rosa Watt McGill shows the same romantic spirit that was characteristic of her husband. "My children are happily married and settled away from me," she writes. "The life of the past is too intense to be forgotten". [11]

In the News

- GOLD-SEEKERS OF THE FIFTIES. AFTER EUREKA. HOW THE LEADERS ESCAPED.

- While the victors of Eureka were removing the dead, the wounded, and the captured from the stockade, Peter Lalor, the diggers' leader lay under the pile of slabs in which he had been hidden, bleeding from the wound in his arm. A musket-ball had shattered the bone close to the shoulder, and the few who knew where he was lying saw the blood trickling from beneath the pile of slabs even while the soldiers, keen to capture him, were still in the stockade. When the last of them had gone Lalor was helped from his hiding-place, put upon a white horse, and rode away through the bush towards Warrenheip. There he claimed shelter at the hut of a man he knew. The digger was absent, and his wife went to look for him. Lalor, however, doubted her genuineness, and believing that she had gone to communicate with the police, he took to the bush again for shelter. All that night he wandered about, with his crushed arm still swinging useless and unattended. He was greatly weakened from loss of blood, and only his indomitable pluck kept him up. Towards morning he determined to seek assistance from Stephen Cummins, an old friend whom he could trust, and who lived with his wife on Pennyweight Hill.

- It was on the early morning of the Monday following the fight that Mrs. Cummins drew her husband's attention to a man walking slowly between the holes on the flat, and said, "That is Peter Lalor; I feel sure of it." "As I ran down to help him,"

- Steve Cummins told a friend, "his face was grey and worried. He looked like a frail old man rather than a powerful young one, so greatly had pain and loss of blood during the 24 hours weakened him. I helped him into the hut, where as well as we could my wife and I bandaged the wounded arm. I knew that my hut was no place for him. A reward of £200 had been offered for his arrest, and there were many mean spirits keen to earn it. Our friendship was well known, and I felt sure that sooner or later my place would be searched by the Police. I ran at once across the gully to the Roman Catholic Presbytery and told Father Smyth that Lalor was in my tent badly wounded and in need of surgical assistance. I told him my fears as to the police visiting us, and Father Smyth said, 'He will be safer here, I think. Bring him over after dark.' so that night we took him across to the presbytery, meeting, fortunately, not a soul upon the road."

- Steve Cummins's intuition had served him well, for next night the police searched his hut, just at the time when he was watching Drs. Doyle and Stewart amputating Peter Lalor's arm, for the severity of the wound and the delay in treating it precluded any possibility of the arm being saved. Through the ordeal of amputation, as in every other emergency of life, he showed that fine courage which nothing could shake. He was a stalwart who knew no fatigue, as it was ordinarily understood, and long before he became a prominent man in Ballarat it was frequently his custom to walk to Geelong to see his sweetheart, and then walk back to his work again.

- A man employed about the Presbytery took the severed arm away as soon as the operation was over, and threw it down an abandoned shaft, but by Father Smyth's orders it was recoved later and properly buried. The first operation was not complete. A portion of the bullet remained lodged in the stump of the arm, and it was only after a second operation at Geelong that the wound healed properly. When the wounded leader had sufficiently recovered to move about he and Hayes, one of the fire-eating orators of the Diggers' Reform League meetings, were taken to a store near Brown's Hill, where they were safely sheltered until a chance of getting clear away from Ballarat should present itself.

- Lalor's escape was greatly aided by a carrier named Michael Carroll, who died at Geelong within the last few months, and whose son is still living in Ballarat. They used to bring up loads of goods and hawk them on the diggings. "One day," says the younger Mr. Carroll, who was then but a boy, "we stopped at the hut of an old friend of my father's, Michael Hayes (not the orator, Timothy), and yarned about old times. There was a piece of green baize hanging at one end of the hut, but I did not guess then that there was anyone behind it. As soon as we left the house it seems Lalor, knowing that my father had come from Geelong, asked if we could be trusted. Mrs. Hayes told him that we could, and we were called back to the hut. On going in we saw that the baize partition had been drawn back, and Lalor was sitting on a stretcher. 'Do you know who I am?' he asked. 'Yes,' my father said, 'you are Peter Lalor.' He asked us to take a letter down to Geelong to Miss Dunn, the school-mistress, the lady whom he afterwards married, and it was arranged that we should take Lalor himself down on the succeeding trip. I remember the great secrecy that was observed, for there were troopers up and down the roads every day, and all over the country, most of them alert for any trace of the Eureka leaders. Nearly every dray on the roads had a small tent fixed upon it, so we cut some whipsticks, and formed a tilt on one of our drays over which we hung a tarpaulin. One Sunday morning I took the tilted cart down to Hayes's tent, and with several men on the watch, in case of surprise, we took Lalor down by Eureka, and across towards Warrenheip, stopping for for a while at Steve Cummins's tent. We went away out by the Green Hills, having determined to take the back track all the way to Geelong, to travel by night only and camp in the bush during the day.

- "Lalor walked most of the way, keeping a bit out from the track in the bush, so that in the event of meeting any mounted troopers suddenly he should not be taken by surprise. It has been said that we met police on the road, who asked us about Lalor, and could have seen him sitting in the dray had they been curious enough to lift the flap of the tarpaulin. That is not so, for the only adventure we had was on the second morning of the journey.

- "Lalor was not yet quite recovered from his wound, and had been supplied with some wine for use on the road. As the weather was very hot the wine was finished by the time we reached Lethbridge — then known as the Muddy Water Holes. In the early morning, therefore, my father went across to the Separation Hotel and roused up the landlord to get some more wine. As he was returning to the drays he met two men who had been camped under a tree rolling up their swags, and one of them, named Burns, whom we knew, asked for a 'lift' into Geelong. My father put him off with the excuse that he intended to load up with some wood a little further on, but as they passed the dray in which Lalor sat, Burn's mate caught a glimpse of him. 'Did you notice who was under that tarpaulin?' he asked, 'It was Lalor, the Eureka man. Now, there's a big reward offered for him, so I intend to follow the drays quietly to Geelong, put the police on to him, and get the reward.'

- "Burns was a genuine fellow, with no taste for such dirty work, so he determined to baulk his mate, and to do it the more effectually he pretended acquiescence. 'It's a good thing,' he agreed; 'don't say a word about it. We'll go and have a drink on the strength of it.' They got a bottle of whisky, and Burns gave his mate such good measure that he was soon hopelessly drunk. Leaving him at the hotel Burns ran across to where we were camped, and said to my father. 'For God's sake get Lalor away as quickly as you can. My mate has recognised him, and he's going to lay the police on to you. I'll keep him drunk until you get away.' We were rather anxious after that, especially when going down the main road, but we landed Lalor at Miss Dunn's place at about one in the morning, and he was afterwards taken to the Queen's Head Hotel in South Geelong.

- "Lalor chatted frequently with my father about the Eureka fight on the way down. It was not easy, indeed, to avoid the subject, for nearly every second tree trunk had the proclamation offering a reward for his capture. I heard him say that on the morning of the riot they would have beaten back the soldiers if the diggers had been able to get into anything like proper formation. He tried to get them into order — those with rifles in the front rank for the long range fighting, the revolver corps next for closer work, and the pike men in reserve for a hand to hand struggle. The men, however, rushed pell-mell from the tents when alarm was given, and were all mixed up together."

- Peter Lalor remained in hiding at Geelong until it was seen that no jury would convict the Eureka rioters, and he then communicated with the Attorney-General, who told him that he was free to go as he pleased. He returned immediately to Ballarat, where he was enthusiastically welcomed, and the diggers, headed by Steve Cummins, collected £1,000 to start him in business.

- It is said, indeed, that Lalor went back to Ballarat while the reward for his apprehension, dead or alive, was still in force, and many thought him greatly daring in doing so. He even attended a public land sale to bid for some allotments, and when the land officer asked "What name, sir?" believing a fictitious one would be given, the rebel of Eureka, in a voice that was of itself a challenge said "Peter Lalor." He looked up his former mate, John Phelan, and the two bought a farm at Coghill's Creek, where he remained until the miners of Ballarat elected him a member of the Legislature. Then began the political career which had its climax in his being six times chosen as Speaker of the Assembly of Victoria.

- The flight and hiding of Frederick Vern for whom the Government, believing him to be the real commander-in-chief at Eureka, offered a reward of £500 — was characteristic of the man. He was given shelter by some miners far out in the ranges. On going to work in the morning they used to leave him in the tent, lacing it up outside so as to give the impression that it was unoccupied. Vern hardly knew whether to be pleased or scared by the fact that £500 was offered for his arrest, and only £200 a-piece for the other leaders of the outbreak. It flattered his vanity that he should be singled out for special notice, but alarmed him lest it should lead to his apprehension. Vern, as described in the proclamation, must have een a somewhat peculiar person - 5ft. 10in, long light hair, falling heavily on the side of his head; little whisker, a large flat face, eyes light grey or green, and very wide asunder; speaks with a strong foreign accent."

- While Vern was in hiding in the diggers' hut they persuaded him to write a farewell to Victoria, as though addressed from Port Phillip Heads, and with the idea of suggesting to the authorities that he had escaped from Victoria. The plan was pleasing to his self-conceit, and its execution a supreme specimen of what Raffaello called "sky blathering." "Farewell, my comrades," he said; "would to heaven I had died with you." "No fear," retorted the Italian, with a juster appreciation of his comrade's weaknesses than his own; "the length of your legs saved you."

- An incident that well nigh cost Vern his life, from fright, closed his occupancy of the digger's tent. On day four troopers were seen riding up to the place. Vern, in a terrible funk, was hustled under the bunk, and the "possum" rug was pulled down so as to conceal him from view. The troopers stayed chatting for some time, and then left. When they had disappeared Vern was helped out. His face was ashy pale, he trembled violently in every limb, and it was some time before he could speak. Vern afterwards got three months in gaol for inciting miners to riot on the Black Lead, at Egerton, and was finally blotted out of publicity by a footnote to one of his own letters in the "Ballarat Star." Mr. J.B. Humffray and Mr. Thos. Loader were contesting Ballarat East, and Vern sought to run with the hare and hunt with the hounds. When his game was exposed he accused Mr. Loader's "myrmidons" of forgery. His letters were compared, their genuineness made manifest, and the editor closed some cutting observations on the incident with "Mr. Vern's courage has become proverbial, his truthfulness is now deserving of an equally honourable distinction."

- Another of the leaders who escaped was James McGill, a young American. After the diggers had been scattered on the summit of Eureka he started through the bush for Creswick, and, according to his own statement, went with the idea of seizing two field guns which were believed to be on Captain Hepburn's estate at Smeaton. He soon learned that not only had the last shot been fired in the diggers' insurrection, but that all his ingenuity would be needed to save himself from capture. Disguised in woman's clothes lent him at The Springs, he travelled by coach to Melbourne on the Tuesday after the fight, meeting on the road the military reinforcements under Sir Robert Nickle marching to Ballarat. George Francis Train, the weird American, who, though now an old man, still keeps himself under public notice by the wide distribution of his addresses and ideas, was then the Melbourne agent for the famous White Star line, and he sent M'Gill on board the Arabian disguised in the dress of an officer, and kept him there for some time. Train interviewed Sir Charles Hotham in M'Gill's interest, and took the young American out to Toorak to see the Governor, who, surprised at his youth, told him to go about his business and behave himself better in future. The only condition was that he should leave the colony at once, and Train, who had a weakness for dramatic effects, got him smuggled as an invalid to the sanitary station at the Heads, where he pondered by the sad sea waves and netted crayfish till the aquittal of the Eureka prisoners left him at liberty to make a fresh start.

- Geelong appears to have been the haven of refuge for which nearly all the fugitives from Eureka made. Esmond was there for some time, as well as Lalor, and it is asserted that the police could have laid hands on both without much difficulty, but they had good friends in the town, and were not molested. Two others of the Reform League leaders for whom a reward was offered — Black and Kennedy — started for Geelong, keeping away from all the recognised tracks. Kennedy, as we have shown in a former sketch, was a Gascon— by impulse. Self-assertive even as a fugitive, he declared that he could find his way to Geelong via the Mount Misery Ranges. Before starting they disguised themselves, each cutting the other's beard off. On the evening of the first day's tramp the self-confidence of Kennedy had reduced itself merely to the conviction that they were lost in the bush. After tramping for some time they blundered upon an out-camp of Ballarat rowdies, where Kennedy wished to be mysterious, but Black told the diggers frankly that they had had a row with the authorities, and were flying for their lives. Soon afterwards they separated, Kennedy going bullock-driving, while Black managed to reach Melbourne, where he was for some time concealed by his friends.

- It is interesting to compare the actual state of things — these solitary escapees trudging nervously through the gloom of the great gum forests, intent only on their own safety, and the state of affairs which distance rumour, or imagination had created in Melbourne. For some time it was rumoured that Vern and his associates were building another stockade in the Warrenheip Ranges. It was even declared that hordes of dangerous and bloodthirsty diggers were marching upon Melbourne, intent only on sack and pillage. Meetings were held in the city, and special police sworn in for its defence. There could be no greater contrast than between the rumoured and the real.

- It is a singular thing that many of the men who took a leading part in the Eureka riot made a bad end. One was subsequently convicted of felony; one was killed by a fall of ground in a mine; a third fell from his horse near Kingston, and broke his neck; a fourth died in the Melbourne Hospital; a fifth in the Inglewood Hospital; a sixth in the lunatic asylum at Kew; while another committed suicide.[12]

- RENEWING THEIR YOUTH.

- Scene.—The horse parade in Armstrong street. Time.—Saturday, loth September, 1888. They were old mates—three of them.

- They had not met since I856 —fine stalwart young fellows then; old grey beards now of 50 and upwards. “Charley, old man, is that yourself? Hullo; is that you, Mick?” They grip, aud hold on, while giving forcible ex pression to their surprise and pleasure of meeting. “Come and have a drink.” One of them had just come down from Northern Queensland, the other was farming in the north-eastern district up beyond St Arnaud. The drinks were just tabled when a rousing whack on each of their shoulders faced them round to discover a third old mate. Bill, now a retired cattle salesman from the Western district. More hand-gripping and more drinks, followed by loud talking about old times and the beautiful fools we used to be when Ballarat was young. Let’s go down to the " Old Charlie” and have a general look round was voted unanimous. But the “ Old Charlie” was gone; John Chinaman was in possession. Shades of Thatcher; don’t we remember how he used to sing— “ John Chinaman my Joe John, You're coming precious fast, And every ship from Shanghai Brings an increase on the last; And you’ve got a butcher's shop, John, At your encampment down below, And you likes your cutlets now and then, John Chinaman my Joe.” John o’ Groats had disappeared; the Union Tent was no more; here the comic Morris brought down the house nightly with double success, while Miska Hauser's sweet music failed to reach the fancy of the noisy majority, fiddle he never so divinely. Herr Ralim, the great Tyrolese minstrel, decorated in highly fantastic costume, fared but little better. The double gum tree, where Big Larry lauded Lady Hotham across the diggers’ holes, has gone to decay; the House of Blazes is no more, and the old Duchess of Kent—oh where, and oh where is she gone? Every night her sweet tenor contralto wound up the ball with the declara tion that For bonnie Annie Laurie I’d lay me down and dee. That was the signal to shut up shop. Well, take her for all in all as times weut, she wasn’t a bad old sort; let’s go and driuk her health. Up Eureka way they light upon the Free Trade hotel and call for nobblers round. They move on; here’s the spot the traps dropped on us for our licenses. We made a run for it right across the gully, and you, Charley, got bogged going round over there by O’Connor’s T store—two great T’s, one black and one green. Yes, and you blessed fellows kept shy while me and a lot more was herded in that blessed Camp waiting for Cocky Reid to wash down his grub with some poor devil’s forfeited sly grog before he would condescend to come out and fine us for leaving our licenses in the tent in the other trousers pocket. Lucky for me Terrier Jack had notes enough about him to pay for both. Talking about Terrier Jack, do you mind when he was sitting down on the top of the shaft in front of Mrs Denny’s saloon he slipped off and dropped into the well 80 feet, got into the bucket, and shouted to wind up. Didn’t he swear, though. Jack was a plucky little chap. When the tiger got away from the travelling menagerie and took shelter in the crockery shop there was a commotion and no mistake. Jack got up on the ridgepole and lassoed Mr Tiger in quick sticks. The showman gave him 10 notes. We had a grand carouse that night—oh, what jolly old fools we were in those days. Let’s move on, and here’s where Bentley’s was— don’t some of us remember the pretty barmaid—eh, Bill, old man? You was a bit gone there—now, don’t deny it. I was sweet on that lot myself, but didn’t care to run an old friend too close; things used to go pretty-high at Bentley’s. Black Ferry, Flash Bourke, Tip M’Grath, and that crowd; aud there was Bob M’Laren and Mat. Hardy, and old Emery’s bowling saloon—oh Lord, what games we used to cut here in the old times! Hornpipes, jigs, strathspeys, and reels Put life and mettle in our heels. And the noble art wasn’t neglected. I thought we was in for it that night when Mick knocked Black Ferry over three times running. The nigger did not understand the Cornish tip of the toe close under his ankle bone, but he came up smiling, aud a liberal call on the waiter made things pleasant. Well, Bentley made a fine bonfire, and none too soon, for it was the devil’s own shop. The acquittal of Bentley, “ without a stain upon his character,” by Police-Magistrate Dewes, for the murder of Scobie, created tremendous indignation, and little Kennedy kept stirring the fire until the authorities ordered a new trial, and Bentley was committed for manslaughter. Ah, well, Scobie was no hero, only the martyr of his own folly. And here is the Stockade of the 4th of December, 1854. It is a long time since we were here boys, but to my mind this monument is too far up the hill. Look, yonder is where Captain Wise came on with the 40th, and around here the troopers dashed through the slabs, and soon made short work of it. Little Thoneman, the lemonade man, was shot, bayonetted, and sabred here on the right of the gully, and over there on the left lay the German blacksmith who made the pikes, with the top of his skull hanging by the scalp, and still living, his little terrier dog lying on his breast aud refusing to leave his master. It was a sorry sight that blackened the hillside on that bright Sabbath morn, with the bodies of 30 stalwart, mostly mis guided, men. Where are the patriots to-day who goaded them on — Kennedy, who declared there was no argument equal to a “lick under the lug,” was not to be found in the stockade when the licking had to be done; poor fellow, he was killed by a fall from his horse at Kingston. George Black, the chief’s aide-de-camp, died in the Melbourne Hospital; his brother Alfred, secretary for War, was killed by a fall of ground at Staffordshire Reef; Tim Hayes died in the Lunatic Asylum at Kew; Mulholland served the Government for some time against his will; Jim M’Gill fills a pauper’s grave at Inglewood; Lalor and Humffray are still with us; let them speak for themselves, and say if they are satisfied with the past and content with the present; but we move on across the Red Hill to the place where once stood the Sir Charles Hotham hotel and the arena where Bill Hodge and Tom Cawse, Jack Botherras, and Collie Bray and other notable athletes contended for the belt —no Greco-Roman strangling hammerlock brutality, but scientific heel and toe play, with Doctor Gibson up as referee; back through the Canadian, Prince Regent, and the jeweller’s shop, down the Red Streak to the Gum Tree Flat and Navvy Jacks, through the lane between old Grimley and the Gasworks the approach Yale’s corner, where Mick raised the cry of “Joe, Joe,” and “Traps, traps,” “Look out boys, here they come,” but it was only a squad of Oldham’s State school cadets going home from drill. Decent lads these, said Charley, not ashamed to take off their shirts or turn up their trousers; no tatooing on their back or bracelet souvenirs on their ankles. The squatting nominee Government of the old days have a multit ude of sins to answer for, but their reign has passed away, the working man is our god to-day, aud he is a hard task-master in his Newcastle. Up the Camp Hill to Bath’s, they call for nobblers round three times. Good-bye, hic—good-bye, old fe-fella; who can tell when we three shall meet again ?[13]

See also

Independent California Rangers

Further Reading

Corfield, J., Wickham, D., & Gervasoni, C. The Eureka Encyclopaedia, Ballarat Heritage Services, 2004.

References

- ↑ Corfield, J.,Wickham, D., & Gervasoni, C. The Eureka Encyclopaedia, Ballarat Heritage Services, 2004.

- ↑ Corfield, J.,Wickham, D., & Gervasoni, C. The Eureka Encyclopaedia, Ballarat Heritage Services, 2004.

- ↑ The Argus, 21 August 1937

- ↑ Evening Echo, 1904.

- ↑ Blake, Gregory, To Pierce the Tyrant's Heart, Australian Military History Publications, 2009, p.212.

- ↑ Blake, Gregory, To Pierce the Tyrant's Heart,Australian Military History Publications, 2009, p.212.

- ↑ Blake, Gregory, To Pierce the Tyrant's Heart,Australian Military History Publications, 2009, p.212.

- ↑ Ballarat Courier, 13 December 1883.

- ↑ Ballarat Star, 5 May 1857

- ↑ The Argus, 4 May 1943.

- ↑ The Argus, 21 August 1937.

- ↑ The Argus, 1 July 1899.

- ↑ Ballarat Star, 22 September 1888.