Eureka 2008

EUREKA UPRISING: 154th ANNIVERSARY 3 December 2008 Celtic Club Melbourne

How things change…

It is no surprise that, in the aftermath of the rising on 3 December 1854, 12 of the Eureka rebels were put on their trial for treason. The first tried was John Joseph. He was acquitted and was carried around Melbourne in triumph. Thousands welcomed his acquittal. The others were acquitted soon after.

If the same things happened in Australia today, it would work quite differently. The Eureka rebels would be charged with terrorist offences. The offence of terrorism includes threatening, planning, urging, inciting or carrying out a terrorist act. A terrorist act includes acts which cause serious damage to persons or property and which are done with the intention of advancing a political, religious or ideological cause, unless it is advocacy, protest, dissent or industrial action which was not intended to cause serious harm.

The trial of John Joseph started on 22 February 1855: just a couple of months after the events which we celebrate tonight. If modern day Eureka rebels were charged with terrorist offences, they would languish in Barwon prison for a couple of years before eventually coming to trial. They would be held in solitary confinement most of the time; they would be transported to and from court shackled in the back of a prison van; they would be strip searched each time they had a visitor in prison. Their lawyers would have to be security-cleared to be allowed to see the evidence.

Those who celebrate Eureka each year should notice these unhappy changes in our society: dissent is not as free as it used to be. And those who celebrate Eureka each year should consider the ominous possibilities of a gathering like this. The Criminal Code provides for terrorist organisations to be proscribed by regulation. An organisation can be listed as a terrorist organisation if it “advocates the doing of a terrorist act”. An organisation advocates a terrorist act if it “directly praises the doing of a terrorist act in circumstances where there is a risk that such praise might (cause) a person (regardless of his or her age or any mental impairment … that the person might suffer) to engage in a terrorist act.”

So, if celebrating Eureka might give a half-wit the idea of staging a similar revolt, we are advocatig terrorism.

What did it mean?

The significance of Eureka has been interpreted by many people in many different ways. It has been characterized as a “right wing small business revolt” (Tim Fischer); “an earnest attempt at democratic government” (Sir Robert Menzies); “the birth of Australian democracy” (Doc Evatt); “a demand for fairness and equality” (Robert Doyle); “similar to the Tiananmen Square massacre” (Bernard Barrett); a quest for “independence, freedom, unity, hope” (Clare Wright); “the finest thing in Australian history – a revolution, small in size but great politically” (Mark Twain); “a fight for human rights, justice and tolerance” (Steve Bracks).

The historian Geoffrey Serle observed that “no final conclusion can be drawn” about the meaning of Eureka. That great political pragmatist Gough Whitlam said that its “importance lies not in what happened but what later generations believed to have happened”.

The common theme in many of these observations, and the undeniable historical fact, is that it involved a demand for a fair go and a demand for democratic representation. Certainly, it was a protest against the unfairness of a harsh tax imposed on people who had no opportunity of a voice in government.

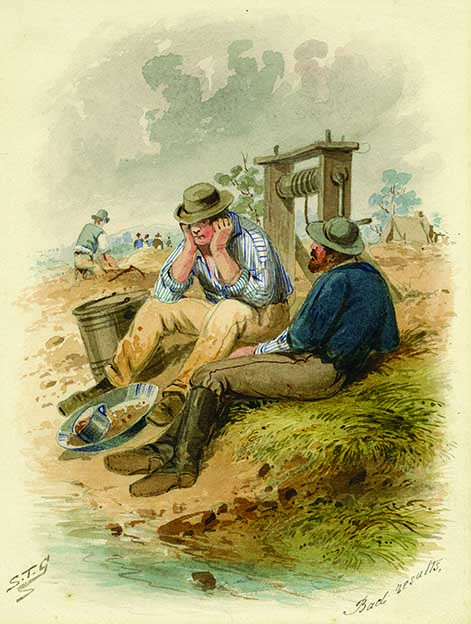

The roots of Eureka lie deep in the soil of many other nations. The miners who had come to the goldfields of Ballarat in immense numbers over the previous few years came from America, Ireland, Scotland, France, Russia, Spain, Germany and other places. They brought with them memories of oppression and of revolution.

In 1854, the French Revolution was a matter of living memory. The Great American Experiment was not yet a century old, and would not face the test of civil war until eight years later. Those who came from Europe knew how fragile the idea of democracy was. Those who fled Ireland knew the reality of mass starvation under an uncaring government.

The origins of Eureka have been traced as far back as Magna Carta.

Magna Carta, (1215)

[12] No scutage or aid shall be imposed in our kingdom unless by common counsel of our kingdom, except for ransoming our person, for making our eldest son a knight, and for once marrying our eldest daughter, and for these only a reasonable aid shall be levied. Be it done in like manner concerning aids from the city of London. (scutage was a tax levied on knight's fees; chiefly such a tax paid in lieu of military service. Magna Carta was mostly concerned with things other than taxes. For example, article 50: We will remove completely from office the relations of Gerard de Athée so that in future they shall have no office in England)

Locke 2nd Treatise on Government (1690)

134. The lawful power of making laws to command whole politic societies of men, belonging so properly unto the same entire societies, that for any prince or potentate, of what kind soever upon earth, to exercise the same of himself, and not by express commission immediately and personally received from God, or else by authority derived at the first from their consent, upon whose persons they impose laws, it is no better than mere tyranny. Laws they are not, therefore, which public approbation hath not made so." Hooker, ibid. 10. "Of this point, therefore, we are to note that such men naturally have no full and perfect power to command whole politic multitudes of men, therefore utterly without our consent we could in such sort be at no man's commandment living. And to be commanded, we do consent when that society, whereof we be a part, hath at any time before consented, without revoking the same after by the like universal agreement. "Laws therefore human, of what kind soever, are available by consent." Hooker, Ibid.

140. It is true governments cannot be supported without great charge, and it is fit every one who enjoys his share of the protection should pay out of his estate his proportion for the maintenance of it. But still it must be with his own consent- i.e., the consent of the majority, giving it either by themselves or their representatives chosen by them; for if any one shall claim a power to lay and levy taxes on the people by his own authority, and without such consent of the people, he thereby invades the fundamental law of property, and subverts the end of government. For what property have I in that which another may by right take when he pleases to himself?

US Declaration of Independence (1776)

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.--We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,--That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. …

The Eureka Declaration Resolved at the meeting of 11 November 1854

That it is the inalienable right of every citizen to have a voice in making the laws he is called upon to obey – that taxation without representation is tyranny.

That, being as the people have been hitherto, unrepresented in the Legislative Council of the Colony of Victoria, they have been tyrannised over, and it becomes their duty as well as interest to resist, and if necessary to remove the irresponsible power which so tyrannises over them.

That this Colony has hitherto been governed by paid Officials, upon the false assumption that law is greater than justice because, forsooth, it was made by them and their friends, and admirably suits their selfish ends and narrow minded views. It is the object of the “League” to place the power in the hands of responsible representatives of the people to frame wholesome laws and carry on an honest Government.

That it is not the wish of the “League” to effect an immediate separation of this Colony from the parent country, if equal laws and equal rights are dealt out to the whole free community. But that if Queen Victoria continues to act upon the ill advice of the dishonest ministers and insists upon indirectly dictating obnoxious laws for the Colony under the assumed authority of the Royal Prerogative the Reform League will endeavour to supersede such Royal Prerogative by asserting that of the People which is the most Royal of all Prerogatives, as the people are the only legitimate source of all political power. A contemporary reading

Locke had earlier introduced, and the Declaration of Independence had implemented, the idea that the only legitimate source of the power of government came from the consent of the governed. Anyone for an instinct for justice could see that it was unfair in a profound way to impose a crippling tax on people who could ill-afford it, and who had no say in government. So while the trigger for the uprising was the mining licence, it was equally about the unfairness of a government which ruled without consent and taxed those who had no vote. Some see this as Chartism, which it is; some see it as a call for democracy, which it is. Some see it as standing up for the idea of a fair go: and so it is. The difference between these views lies only in the level at which you analyse what impelled a small group to take a stand on the 3rd December, 1854.

I am attracted to the analysis that Eureka expressed the deep human need for a fair go, for people to be treated decently and fairly regardless of their station in society.

Taxation without representation is not a problem these days, but the idea of a fair go for all is. The Australian idea of a fair go turns out, on examination, to be a bit uneven. While most Australians would say they believe in the importance of human rights, they might have trouble explaining how it is that we watched with unconcern as Mamdouh Habib and David Hicks languished in Guantanamo Bay for years, their fate ignored by the Australian Government. They might not be able to explain how, for years, we closed our eyes to the awful sight of men, women and children locked behind razor wire, innocent of any offence, but held for months or years in hopelessness and despair. We mistreated innocent people in order to send a message. It was irreconcilable with even the simplest notion of a fair go.

We waited a very long time before a government was willing to acknowledge the self-evident point that taking Aboriginal children from their parents had been a terrible moral wrong which caused terrible damage and pain.

On closer examination, our dedication to human rights looks rather like a more limited idea: we think our own human rights matter, and those of our family and friends and neighbours. But the human rights of minorities we despise or fear matter much less. Perhaps we think their humanity is not of the same order as ours.

The argument about a Bill of Rights

At the 2020 Summit in Canberra earlier this year, a view emerged strongly that Australia should have a Federal Bill of Rights. That call – fairly predictable in the circumstances – triggered a series of public speeches and papers as Cardinal Pell, Bob Carr and others raised their voices against a Bill of Rights.

These pre-emptive strikes against the possibility of a Federal Bill of Rights had one thing in common: they did not identify what sort of Bill of Rights they are opposed to.

Some of their criticisms might be valid if the proposal was for a US-style Bill of Rights. So far as I am aware, no-one in Australia is pushing for a US-style Bill of Rights. The US Bill of Rights is an 18th Century document with its roots in 17th Century England, and a dash of Magna Carta providing the best bits. To make the debate intelligible, it is useful to identify what we are talking about. We are not talking about a US style Bill of Rights. Some people prefer to speak of a Charter of Rights in order to make the distinction plain. Nevertheless, it is worth bearing in mind that there is no magic in the name: a Charter of Rights and a Bill of Rights are the same thing; the US Bill of Rights is an early example, but it is not one to be emulated. The US Bill of Rights is an 18th Century document with almost nothing in common with modern bills of rights. The rights protected by a modern bill of rights are – broadly speaking – the sort of rights addressed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which Australia adopted in 1948. It would be difficult to find any serious disagreement about the nature of those rights – freedom from arbitrary detention, freedom from torture, freedom of thought and belief, equality before the law etc. The disagreement arises when the means of protecting those rights is in issue.

Broadly speaking, a modern bill of rights can be a weak model or a strong one; and it can be an ordinary statute or constitutionally entrenched. The arguments for and against a bill of rights change profoundly according to the model under discussion. Unfortunately, the conservative commentators never identify exactly what it is they are condemning. Statutory bills of rights can be disregarded or repealed if the Parliament so wishes. A constitutional bill of rights, on the other hand, cannot be repealed or altered except by referendum. A constitution (in theory) expresses the will of the people directly, and binds the Parliament. A statute, by contrast, expresses the will of the people indirectly through their elected representatives and can be made, changed or repealed by the Parliament. A strong model Charter creates rights of action: if a person’s rights are breached, they may be able to sue for damages. A strong model may also forbid Parliament to do certain things and thereby directly limit the power of the Parliament. A weak model simply requires Parliament to take protected rights into account when passing legislation. If they wish to disregard those rights, they must say so plainly. This means that the Parliament will be politically accountable if it decides to disregard rights which it has previously resolved to respect. In addition, it guides Judges in the way they should interpret legislation, so as to preserve rights rather than defeat them.

The ACT and Victoria both have statutory, weak Charters of Rights. So long as the public and the conservative commentators find it alarming to protect rights, a weak statutory model is a good solution. It is usual to see a range of arguments put up against adoption of a Bill of Rights. The standard ones are as follows: (a) Our rights are adequately protected by the majesty of the Common Law; (b) It is anti-democratic because it would transfer power from Parliament to unelected, unrepresentative judges; (c) It transfers power disproportionately to minorities; (d) A Bill of Rights will be a Lawyers’ Feast. Let me deal with each of these in turn.

Our rights are adequately protected

Within the scope of its legislative competence, Parliament's power is unlimited. The classic example of this is that, if Parliament has power to make laws with respect to children, it could validly pass a law which required all blue-eyed babies to be killed at birth. The law, although terrible, would be valid. One response to this is that a democratic system allows that government to be thrown out at the next election. This is not much comfort for the blue-eyed babies born in the meantime. And even this democratic correction may not be enough: if blue-eyed people are an unpopular minority, the majority may prefer to return the government to power. The Nuremberg laws of Germany in the 1930s were horrifying, but were constitutionally valid laws which attracted the support of many Germans.

Generally, Parliament's powers are defined by reference to subject matter. Within a head of power, Parliament can do pretty much what it likes. Thus, the Commonwealth's power to make laws with respect to immigration has in fact been interpreted by the High Court as justifying a law which permits an innocent person to be held in immigration detention for life, where he is liable for the daily cost of his own detention.

The question then is this. Should we have some mechanism which prevents parliaments from making laws which are unjust, or which offend basic values, even if those laws are otherwise within the scope of Parliament's powers? If such a mechanism is thought useful, it is likely to be called a Bill of Rights, or Charter of Rights, or something similar. In November 2003 two cases were heard together by the High Court of Australia . Together they tested key aspects of the system of mandatory detention. One was the case of Mr Al-Kateb . He arrived in Australia as a boat person and sought asylum. He was placed in immigration detention because the Migration Act says that a non-citizen who does not have a visa must be detained and must remain in detention until (a) they are given a visa or (b) they are removed from Australia. He was refused a visa. He could not bear it in Woomera and asked to be removed, rather than wait out a year or two by appealing. But it was not possible to remove him from Australia, because he is stateless: there is nowhere to remove him to. The government’s argument was that, although Mr al Kateb has committed no offence, he could be kept in detention for the rest of his life. On 6 August 2004, the High Court by a majority of 4 to 3 accepted that argument.

The other case, heard alongside al Kateb and decided on the same day, was Behrooz . Mr Behrooz came from Iran, sought asylum and found himself in the endless loop of rejection and appeal and had spent about 14 months before escaping in November 2001. At that time, Woomera was carrying three times as many people as it was designed to carry. The conditions there were abominable. Reports from that time show that there were three working toilets for the population of nearly 1500 people; women having their period had to make a written application for sanitary napkins. And if they needed more than one packet they had to write and explain why they needed more than one packet and very often they had to go and provide the form to a male nurse who would then dispense what they needed. Conditions in Woomera at that time were unconscionably dreadful. The Immigration Detention Advisory Group, the government’s own appointed body, described Woomera as “a human tragedy of unknowable proportions”. Mr Behrooz found it so intolerable that he escaped, along with some others. He was charged with escaping from immigration detention. The defence went like this: The Australian Constitution embodies the separation of powers. This means that the legislative power is vested in the parliament (Chapter I); the executive power is vested in the Executive government (Chapter II) and the judicial power is vested in the courts (Chapter III).

The notion of the separation of powers involves this, that one arm of government cannot exercise the powers given to another arm of government. It is one of the very few constitutional safeguards we have in Australia. Central to the judicial power is the power to punish. As a matter of constitutional theory, punishment cannot be administered directly by the parliament or by the executive, punishment can only be imposed by order of the Chapter III courts. Normally, locking people up is regarded as punishment and therefore it is only Chapter III courts that can lock people up. What about immigration detention? In Lim’s case in 1992, the High Court held that administrative detention may be justified in limited circumstances, principally where detention is reasonably necessary as an aid to the performance of a legitimate executive function. So if a person’s asylum claim is to be processed, or if the person is to be made available for removal from Australia then, as long as the detention is reasonably necessary for those purposes, it will be lawful even though not imposed by a Chapter III court.

Well, the defence in Behrooz went like this. Assuming mandatory detention is constitutionally valid, if the conditions go beyond anything that could be seen as reasonably necessary to the executive function it is said to support then that form of detention will be constitutionally invalid because it amounts to punishment inflicted by the Executive.

We issued subpoenas, directed to the Department and ACM , seeking documents that would reveal details of conditions in detention. They resisted. They said the subpoena was invalid because the conditions in detention will never affect the constitutional validity of detention. And all the way to the High Court they maintained this argument that no matter how inhumane the conditions are, detention in those conditions is nevertheless constitutionally valid.

On 6 August 2004, the High Court accepted the government’s argument.

Thus on the same day the High Court held that it is constitutionally valid in Australia to hold an innocent person for life in the worst conditions human malevolence can devise. In the same year, the High court held that the same principles apply even if the detainee is a child.

These three cases from 2004 are a clear illustration of the problem that, if Parliament decides to make a law which destroys basic rights, the Common Law is unable to prevent that result.

Anti-democratic, because it transfers power to Judges

In one sense, it is true that a Bill of Rights gives power to judges. A Bill of Rights limits the power of Parliament but not by reference to subject matter. A modern Bill of Rights introduces, or records, a set of basic values which should be observed by parliament when making laws on matters over which it has legislative power. It sets the baseline of human rights standards on which Society has agreed. Because this is so, it is wrong to say that a Bill of Rights abdicates democratic power in favour of unelected judges. Judges simply apply the law passed by the parliament. That is their role. Many cases raise questions about Parliament's powers. Judges are the umpires who decide whether Parliament has gone beyond the bounds of its power. A Bill of Rights is a democratically created document, like other statutes. Enforcing it is not undemocratic at all.

Protecting unpopular minorities

One of the most surprising objections to a Bill of Rights is that it gives disproportionate power to minority groups. At one level, the complaint is accurate. In Australia today, the people whose human rights are at risk are not members of the comfortable majority, but members of minority groups who are typically powerless and often unpopular and almost always politically irrelevant. Whilst, in terms, a Bill of Rights protects the rights of all, its primary use is to protect the rights of the weak because the strong are already safe. The criticism is all the more surprising when you consider that many of those who advance it proclaim themselves to be devout Christians. I had thought, although I haven’t checked recently, that much of Christ’s teaching was concerned with the protection of the weak, the unpopular, the despised and the oppressed. It seems a curious thing then that practising Christians should object to a law which achieves that result.

This complaint has a darker side. Broadly speaking, Australians have a fairly respectful attitude to human rights. If most Australians were asked what they thought of human rights they would say that human rights matter. The question then arises: How is it that those same people watched with unconcern as David Hicks languished for years in Guantanamo Bay without charge and without trial? How is it that they watched with unconcern for years as innocent men, women and children were locked up indefinitely in desert jails merely because they were fleeing the Taliban or Saddam Hussein? How is it that we have managed such enduring complacency to the plight of the aborigines whose land was taken and whose children were stolen? How is it that we are so indifferent to the draconian effects of the anti-terror laws as they are applied to Muslims in the Australian community, when we would not tolerate similar intrusions on our own rights?

The answer I think is this: Australians subconsciously divide human beings into two categories: Us and Other. We think, perhaps subconciously, My rights matter, and so do those of my family and friends and neighbours, but the human rights of others do not matter in quite the same way because, (without quite saying it) the Others are not human in quite the same way we are. It is dangerous thinking and profoundly wrong.

We have human rights not because we are nice or because we are white or because we are Christian but because we are human. That’s the sticking point which makes it possible for people to acknowledge that human rights matter and yet resist the possibility of those rights being protected by law.

Lawyers’ Feast

The “Lawyers’ Feast” argument is a popular one, because everyone hates lawyers, and every one loves a feast. Anything which is going to make lawyers happy is a bad thing. The Lawyers’ Feast argument is a coded way of saying that lawyers want a bill of rights because it will generate lucrative work for them. The argument is false. In Australia today, the people who need a bill of rights – the people whose rights are denied or disregarded – are almost always at the margins of society. They cannot afford to pay lawyers. Most human rights work in Australia today is done for no fee. Some is funded so that the lawyers receive some payment, usually a very small percentage of ordinary rates. No-one does human rights work to get rich, because human rights work cannot make you rich.

Conclusion

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was entered into force on the 10th December, 1948 – 60 years ago this year. Doc. Evatt presided over the General Assembly that day. Australia now is the only Western democracy which does not have a Bill of Rights. The last decade at least has shown that we need one. Soon we will have a public consultation about a Federal Bill of Rights. I hope the spirit of Eureka will live on when the public consultation begins. Protecting the rights of people who are powerless, disadvantaged or wretched is what a Bill of Rights is about, and it lies at the heart of what Eureka was about. Let’s get a bill of rights for Australia: it would make the Eureka rebels proud.