Ships

Contents

Excerpts: Conference Presentation, Dr Dorothy Wickham

Under the Southern Cross Conference

Australian Catholic University, 2013.

Organised by Victorian Interpretive Projects Inc. in conjunction with Victorian Association of Family History Organisations.

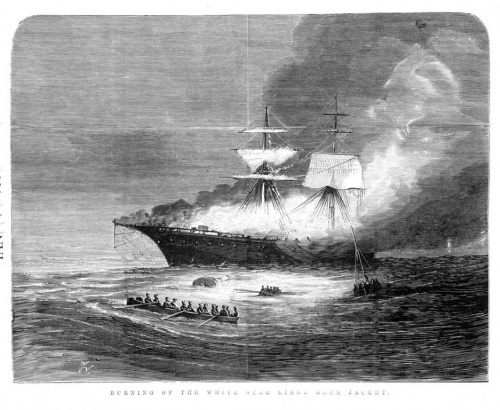

The National Maritime Museum in Sydney, Australia, in their exhibition called PASSAGES brought alive the experience of sea journeys, from the convict era to the modern story of Australia's refugees. Exhibits included diary excerpts, recorded memories, clothing, precious mementos, shipboard souvenirs, and cultural baggage, all avenues by which family historians can trace the voyages undertaken by their ancestors. The exhibits at the Museum explored the various reasons for leaving a homeland, the perils (and pleasures) of the voyage, attachments to home, and the challenges of settling in a new country. In the age of the sailing ship the voyage from Europe to Australia was long, uncomfortable and often boring. For those who chose to make the journey by steerage, accommodation was dark, damp and uncomfortable. Relics from the wreck of the Dunbar (1857) are poignant reminders of the dangers of sea travel. The stretches of ocean and long ship journeys were measured in days, weeks and sometimes months. For those on board, it was usually the longest and most significant journey of their lives.

Routes to Australia

There were two main routes to Australia: the Old Route via Capetown and the New Route known as the Great Circle Route. The new route used the prevailing westerlies and the roaring forties which took vessels down to the edge of the pack ice. This halved the sailing time from the United Kingdom to Australia. The Clippers were so called because they ‘clipped time’ off the route taken. These were faster vessels than the previous barques. They were slimmer: 5 times the breadth in length rather than 4 times.[1]

Immigration

Immigration Schemes were introduced to entice a young population to the new colony.

Free Immigration

Although both the UK and the colonies were keen to encourage migration to Australia in the early 1800s, North America was a more attractive destination, at the end of a shorter and less arduous voyage. To attract prospective settlers to Australia it was thought necessary to provide free or heavily subsidised travel. Posters that were displayed to lure emigrants to Australia. Advertisements noted special provisions for steerage passages and stated that “Families will not be separated”.

A poster advertising Female Immigration in 1836 offered single Irish women “A Free Passage” and the promise that “all who may conduct themselves with discretion and industry may calculate in time importantly to benefit their condition”. It asked, “Do you want to get married?” It also offered “Accommodation with every essential comfort”, immediate placement in employment with respectable families, good wages of the women’s own determination in this “healthy and prosperous colony” and the likelihood of marriage.

From 1839 local officials worked with British Government Officers to promote migration to Victoria and supervise the selection of applicants for both Government and privately sponsored immigration schemes. Assisted immigration schemes developed in response to a demand for labour for the rapidly growing Port Phillip District of Australia. The revenue from land sales funded two main types of assistance: migrant voyages organised directly by the government, and voyages operated by entrepreneurs, who were paid a subsidy or “bounty” for each immigrant on arrival.

Wakefield’s Scheme (Government Assisted Immigration to Victoria) was the one that was adopted for Government Assisted Immigration to Victoria. Wakefield had never been to Australia, but wrote his papers and had them published in a newspaper while he was in gaol. The reason for his gaol sentence was his love of young girls. His first wife was a youngster, an heir in chancery, and when she passed on he inherited her fortune. She happened to be an orphan. He absconded with a second young girl (he was around 29 years of age and she was 15 yrs) but this time he failed to choose an orphan. Her parents followed Wakefield and found the pair in Calais. The parents were most displeased and had him charged and sent to gaol. Wakefield read about the Australian Colonies in gaol and when he wrote his “Letter from Sydney” he was so convincing that most people thought he had actually visited the Colonies.

Private employers could also nominate individual migrants to come to Victoria and they received subsidies for this. They are named in Parliamentary Papers and were referred to as passage warrant holders. The term “assisted” immigrant refers to those who had all or part of their fare to Australia paid by the government under such immigration schemes. In the years to come there were many schemes, and some were even used to rid UK or Ireland of paupers and unwanted souls.

There was great opposition by the Victorian colonists to the idea of convicts and those considered not of high moral standing being given free passages. The colonists even met one of the vessels on the pier that was carrying Exiles into Port Phillip. They confronted them with weapons which resulted in the vessel being turned away, and finally it docked in Sydney.[2]

Immigration Schemes

Maria Rye was more interested in schemes to North America. However, she organised some schemes to Australia to bring out governesses and needlewomen.

Transcription and excerpts from: Florence Chuk, Presentation, Moe Seminar, 5 September 1992.

The Duke of Portland left Gravesend in 1850 with what Captain William Cubitt described as “a parcel o’needlewomen”. The vessel arrived in Port Phillip on 24 August 1850. It carried the third consignment of 60 distressed women sent by Sir Sidney Herbert. Needlewoman was the colloquial term for prostitute, so that this vessel was met at the pier with some interest.

Family Colonisation Loan Society

Caroline Chisholm did much to ease the employment problems of migrants by obtaining firm employment contracts for single women. Later she did the same for married couples. Her Family Colonisation Loan Society advanced money to families to enable them to migrate as whole units.

The Highland and Island Emigration Society Scheme Australia’s needs seemed to coincide with a reciprocal problem in the north of Scotland where much of the population along the west coast was still suffering the effects of near famine conditions which had gripped the region during the previous four years. It was Charles Trevelyan’s grand philanthropic scheme to evacuate the west Highland and Island – especially the Isle of Skye – of their poorest and most redundant population. He thought that 40,000 people could be helped to Australia through the instrumentality of the Highland and island Emigration Society which he had founded with widespread support. The Highland and Island Emigration Society enabled recruitment to Australia to extend into some of the remotest inhabited locations in the British Isles. St Kilda in Scotland lost one third of its population to Port Phillip in 1852/53. These immigrants included some of the poorest, most famished, least industrialised and most marginalised people. Many of these poor emigrants spoke no English, had no money for clothes, and some required special feeding to prepare them for the voyage. Many of them were pathetic economic refugees, some of them begging pitiably for their passages, while some among them had been hounded off their land by landlords.

Orphan Immigration Scheme immigrants came from Irish workhouses. Such schemes as the Donegal Relief Scheme were to place 600 orphans in Adelaide, 1200 in Melbourne and 2300 in Sydney. There was of course opposition to this scheme. The young women were described as ‘dirty brutes’ and the Children’s Apprenticeship Board referred to the ‘extreme filthiness and unimaginable indelicacy of some of these workhouse girls’, while the Melbourne Argus slandered them as ‘the most stupid, the most ignorant, the most useless, and the most unmanageable set of beings that ever cursed a country by their presence’.[3]

Listing of Ships that Brought Passengers Associated with Eureka and Victorian Goldfield Agitation

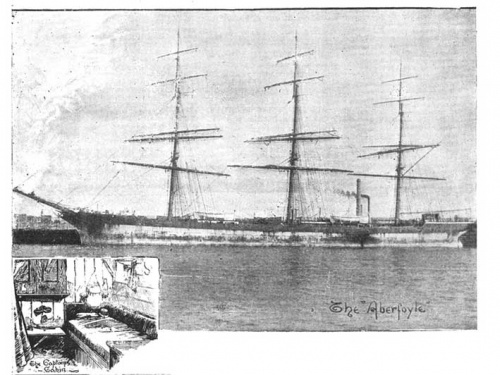

The following vessels brought people associated with the Eureka Stockade, or Ballarat in 1854, to Australia.

Further Reading

https://dorothywickham.com.au/article/a-bowl-of-bitter-tears-immigration/- ↑ Florence Chuk, Somerset Years, Pennant Hill Publishers

- ↑ Dorothy Wickham, An Ocean of Bitter Tears, Under the Southern Cross Conference, Aquinas Campus, Australian Catholic University

- ↑ Dorothy Wickham, An Ocean of Bitter Tears, Under the Southern Cross Conference, Aquinas Campus, Australian Catholic University, 2016.