The Eureka Stockade: Gateway to Democracy

The Eureka Stockade : Gateway to Democracy, by Weston Bate

The Eureka tragedy of 3 December 1854 stemmed from the original government response to the great challenge of controlling an unprecedented rush of people into the bush. These adventurers were seeking the world's most precious metal. Pure gold, in its surface alluvial state, was a social transformer, a democratic mineral. People who found it had cash in their hands. It gave them freedom; perhaps a dangerous freedom. The government was fearful because Californian experience had shown that gold-seekers behaved wildly.

To keep control, sustain the colony's very important pastoral industry and preserve traditional values, Governor La Trobe put in place an emergency system of commissioners, who had both executive and judicial powers. Supported by police and backed up by the military, they became an arbitrary force, whose decisions were hard to challenge. But that was only the beginning of confrontation. To deter men from leaving their normal employment, especially in the pastoral industry, a heavy tax was imposed on all who went to dig. They paid whether they found gold or not. They had to buy a licence, which cost thirty shillings a month - much more than squatters paid to graze sheep on thousands of acres of crown land.

Naturally, the licence tax was opposed from its inception. Notably, a meeting of thousands, most of the colony's men, at Forest Creek (Chewton near Castlemaine) in December 1851, condemned the tax as well as police behaviour when enforcing it. But amazing surface riches there, and at Bendigo soon afterwards, dampened protest until 1853. Then the diggers became impatient. Maladministration at the Ovens field (Beechworth), and seriously declining yields at Bendigo, increased tension. If the governor had not backed down and lowered the tax, the Bendigo "red-ribbon" riots of August 1853 might have brought bloodshed. La Trobe failed, however, to get the conservative Legislative Council to replace the obnoxious tax with a more equitable and less confrontational export duty on gold. In their opposition, the Council, composed of officials, merchants and pastoralists of the pre-gold era, condemned the diggers to the abrasive licence hunts. They left in place an emphasis on social division and official control that would prove disastrous.

During 1852 and 1853, the pastoral era population of 77,000 was flooded by almost 200,000 migrants, drawn by news of Victoria's extraordinary deposits. Among this artisan and generally lower middle-class influx, there were numbers of Chartists, bruised by the crushing of their democratic movement in England. Seeking freedom from old world constraints, they were bound to resent their new bosses, as were a sprinkling of continental revolutionaries, frustrated during encounters with authority in 1848.

By 1854, in segregated "camps", military in style, the administration was set apart. Its officers had been chosen through patronage for their gentlemanly backgrounds. They socialised with the surrounding pastoralists and were mostly unsympathetic to the developing democratic society of which Ballarat was the pacesetter. Since 1852, the Ballarat diggers, becoming experienced miners, had followed buried streams marvellously rich in gold from the surface at the perimeter of the Ballarat East basin into the depths at its centre. They churned up the beautiful resting place (Balla-arat) of the Aboriginal people. A permanent community of about 30,000 was at work. It was a varied population, underpinned by legal partnerships of miners and storekeepers. In an unprecedented union, the former supplied the labour and the latter the capital for hazardous and expensive ventures into the deep, wet ground. It was a giant lottery. Shafts fifty metres deep took as long as a back-breaking eight months to bottom on either "a jeweller's shop" or an unproductive "shicer". One party of twelve took out a massive £6,000 each; others got nothing. Overall though, returns were very good, much larger, at 615,786 ounces than in any previous year.

Complex and stable, focussed on the great challenge, Ballarat was proud of the inventive way double slabs and clay had been used to control great drifts of sand and water in the former lake bed. A sense of community had emerged on what was the most peaceful goldfield until the government system fell apart in September and October 1854. To replace La Trobe the Colonial Office had sent Sir Charles Hotham, a strong-minded naval captain, to tackle mounting government debt, warning him that he might have to fight to maintain the hated licence tax. They missed the chance to tell him to use all his influence to get the Legislative Council to replace it with an export duty on gold. By telling him to stand firm, they foreshadowed a crisis. It was not helped by Hotham's personality. Although a stickler for formal justice, he was two-faced, telling the Ballarat people in August that he would not neglect their interests. He called them lovers of law and order and the whole mining population "a hundred thousand of the finest men in the world". This bred hope that (good for the bottom line) half of what a critic called the "gold-laced gentry and useless officials" would be dismissed. The previously antagonistic Ballarat Times wrote of a new era : "a bold, vigorous and farseeing man has been amongst us, and the many grievances and useless restrictions by which a digger's success is impeded will be swept away".

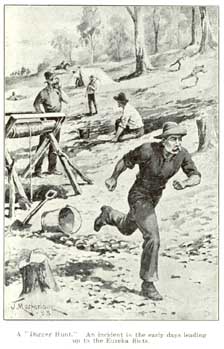

Imagine the disillusionment when on 13 September, against all advice, Hotham ordered twice-weekly searches for unlicensed miners. It was a dreadful imposition on the deep-sinkers, who had to stop work and come to the surface to show licences that were hard to preserve in their watery workplaces. The move also greatly increased hostility to the undermanned, overworked and unsavoury police force, who were motivated by the reward of half the fines imposed on convicted licence dodgers. Many constables were alcoholic ex-army veterans. It was logical to search often, because the law had been liberalised in December 1853 to allow miners to take out one, three, six or twelve month licences on any day of the month. A licence examined one day could be void the next. The majority, holding three month licences, were disaffected by frequent and crude confrontations with the police. They were also indignant because new mining regulations allowed them quite inadequate claims. They had argued and hoped for larger areas, but parties of twelve, necessary for the unending labour, were allotted only four standard claims. Disputes about boundaries were also contentious, decided summarily by commissioners, who were thought to lack expertise and sometimes to show bias. When there were such high stakes, tempers were frayed. Several times in September 1854, the Gravel Pits diggers went on strike.

Discontent over the licence has misled historians like Geoffrey Blainey to overemphasise the significance of the tax in causing the Eureka uprising. Although the later burning of licences suggested that they were the issue, larger complaints were emerging that made licences, although symbolic, a minor factor in the unrest. They were burnt because they were the most visible evidence of government oppression.

The seeds of disaster, sown into that soil, can be identified as a series of miscarriages of justice, latent in the system. First, the Irish, distressed during September and early October by lack of success in finding gold on the Eureka lead, were angered when their priest's servant was unfairly and summarily convicted of resisting police, who had no right to detain him. Then the Americans were offended. One of them, a storekeeper, was arrested by corrupt police on a typically trumped-up grog charge - for which they received half the £50 fine. But these were incidental compared to the deep-seated distrust that followed a serious miscarriage of justice over the murder of James Scobie, a young Scot, by James Bentley, the unsavoury, ex-convict owner of the Eureka Hotel. Bentley was widely suspected and later convicted for the murder, but his friend, the Police Magistrate, John D'Ewes, and the Resident Commissioner in charge of Ballarat, Robert Rede, exonerated him. Uproar followed. Distrust of officials escalated. Their bias was so clear that a protest to condemn their decision and confront Bentley was held at the hotel on Tuesday 17 October.

What happened that day led to the stockade. Probably, because Rede was compromised by the Bentley verdict, the authorities behaved indecisively when protesters began to throw stones at the hotel. They broke windows and started to pull it apart. The police and military stood back. The junior officer appointed to read the riot act failed to do his duty, and Rede was humiliated when he appeared belatedly at a broken window to call for order. Eggs were thrown at him. At about that time, the hotel's very combustible bowling alley was set alight. Before long the whole place was ashes. If Bentley had not escaped on horseback to find refuge at the government camp, who knows what treatment he would have received. He was given a government mount and told to show himself and draw off the crowd, but squibbed the challenge.

The burning of the hotel was a turning point for both sides. D'Ewes, and probably other officers, who frequented it, had invested in the business. The camp was shocked. Rede wrote to Melbourne about his determination to arrest all concerned and if they resisted (what else?) "to teach them a fearful lesson". This injudicious language suggests that he was bent on revenge. Yet, despite his belligerence, "all concerned" amounted only to three - obviously scapegoats - who were arrested and sent for trial. Amid intense anger and doubts about the authenticity of the charges (especially against one of the burners) a committee was formed to raise funds for their defence. They wanted to provide bail but Rede set it at a massive £500 for each man, plus a similar surety. He stood his ground when the amount was queried by a senior magistrate sent up from Melbourne. To Bentley, when finally committed to trial for murder, he allowed bail of £200 and £100 surety. Rede asked urgently for troop reinforcements, saying that the government must be able to "insist". He saw that coercion would be needed when searching for licences and wanted to "test the feelings of the people" with the next hunt.

Why didn't the governor rein in his subordinate? Probably because Hotham had been told to expect a fight. He was conditioned to believe that the fault lay with the rioters - the peaceful Ballarat people he has praised. To let him know how they felt and to let off steam, on Sunday 22 October, ten to fifteen thousand people gathered on Bakery Hill. Nothing like it had been seen before. They passed three resolutions. The first called for funds for the defence of the those arrested. The second condemned the daily violations of personal liberty, while the third laid the blame for the hotel burning on the officials. Cuttingly, official partiality and maladministration were stressed in each resolution. Afterwards, a committee, formed to advance the cause, began sitting at the Star Hotel. In due course, as the struggle for rights increased, that committee became the Ballarat Reform League.

The disaffection had threatening undertones. The people were so angry that the camp residents felt that they were under siege and might be attacked. Indeed, if a rebellion was intended this was the time to mount it. That Sunday evening a large body of Eureka men was seen moving towards the camp, to scare the authorities with an armed protest. That was not surprising. In the morning the catholic congregation had met after mass to consider how to get redress for the treatment of their priest's servant. They were boiling about the injustice, and being Irish were not likely to forgive it. They were under extreme pressure economically. At the same time (13 September) as Hotham ordered the extra licence hunts, the returns at the Irish dominated Eureka plummeted. The coincidence was dramatic. It was reported on 23 September that not a hole had been bottomed on the buried stream for five weeks. Some mining continued, but the population of the "lead" (the name given to buried streams) was reduced to a tenth of what it had been. Taking their vital capital, storekeepers had moved to the booming Gravel Pits. Anger at the government was magnified by despair, as well as fuelled by age-old Irish grievances. Early in October, things were little better. The stream they sought was narrow and constantly twisting. Gold was hard to find.

Although blind to problems with the licence tax, Governor Hotham was consistent in his adherence to the law. On 30 October, he ordered an enquiry into the circumstances surrounding the burning of Bentley's Hotel. It sat between the 2nd and 10th of November, chaired by a Melbourne magistrate. At the same time the burners were being tried at Geelong. Both proceedings produced revelations that justified the people's position. The enquiry condemned the police magistrate, D'Ewes, and Milne, the sergeant major of police, for corruption; and the Geelong jury added to their guilty verdict the damming comment that their duty would not have been necessary if the authorities had done theirs.

Hotham sacked D'Ewes and Milne, but was not swayed by the jury's opinion when the fate of the supposed hotel burners became critical. He lacked the political nouse to hose down the heat. Perhaps he did not care. He failed to go to Ballarat to meet the people again and find out for himself how bad the situation had become so that he could craft a response.

What had been a disconnected set of events, although triggered by the same flawed system of control, became concentrated when the populace responded to the enquiry into the hotel's destruction. They took the opportunity to focus on long-standing grievances. Stark evidence about corrupt and arbitrary behaviour by officials was used to condemn the whole system. More than that, at its 1 November mass meeting, the newly formed Ballarat Reform League moved beyond specifics to the general issue of representation. Inspired by men who had taken the same stand in Britain in 1848, they produced a colonial charter, calling not only for the redress of present grievances but also for a properly democratic constitution. Delivered as a remonstrance in the great British parliamentary tradition, it stressed the denial of civil rights and called for manhood suffrage, vote by ballot and payment of members of parliament - the cutting edge of democracy.

Justifiably angry, the Ballarat people were on fire with ideas about good government. In its condemnation of the existing system, the Ballarat Times printed challenging editorials. And the Reform League justified its stand by referring to a power and right vested by God in the people. They thought that they should be listened to, not stamped upon. Clearly, the enquiry had shown them to be right. Clearly, the government should take notice.

At this critical time, Hotham failed to accept the recommendation of the Board of Enquiry that the licence should be abolished and the police returned to normal work. He used the delaying tactic of a royal commission. (Too late to save the situation, it was to criticise profoundly the structure he left in place.) Not prepared to give ground, he set a course towards tragedy, finding refuge in the view that he had to maintain the law - much derided though it was, and within his power to propose amendments. The elements of confrontation remained and Rede retained the power to provoke with a licence hunt. The tragedy lay in waiting thanks to official blindness and stupidity.

History must ask why the governor gave no credit to previously placid Ballarat. More than that, while the Board of Enquiry was sitting at Ballarat, Rede was in Melbourne getting close to Hotham. Building on well-founded fears of an uprising, they had failed to check, they arranged to use cipher for completely private communication. Hotham by-passed those who counselled caution by using a highly prejudiced man as his agent. How closely they influenced each other cannot be determined. No ciphers survived. But the fact that the man in charge, who should have been made accountable for the failures of the Ballarat administration, was to be the governor's henchman at a time of crises, made a bad situation much worse.

In their righteous indignation, the people did not let up. By a single vote at a committee meeting, the Reform League decided, on the strength of their belief in the power of the people, to send a delegation to Hotham to "demand" the release of the hotel burners. That peremptory word is a measure of their frustration, as well as of the resolve he was up against. They warned, honestly, that there might be bloodshed if he stood his ground. It was not a threat, but he was frosty, prepared to make no concession. He put his own dignity above the needs of the colony. By failing to attend to their concern, whatever their effrontery, he took a further step towards the climax only a week away.

The situation at Ballarat was ominous. The Catholic priest told Rede that a thousand armed men (none English) were ready to do battle. Defiantly, some burnt their licences. Rede asked urgently for reinforcements and was answered with a military force of 9 officers and 297 other ranks. He wanted to crush the agitation (it was not understandable to him). He thought Americans were insidiously urging on what he called "the mob" in order to Americanise the colony. It was a fantasy; he had descended into paranoia.

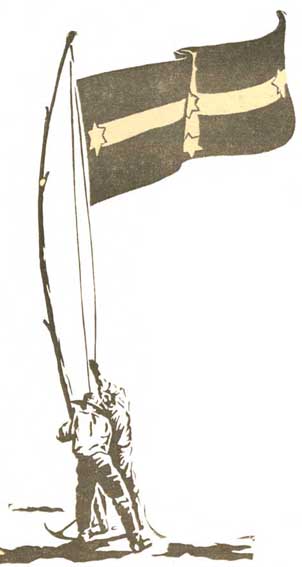

On 29 November, the delegation to Hotham returned empty handed. They were to report at a 2:00pm mass meeting. The committee beforehand (again by one vote) decided to put a motion that licences be burnt. There was hostility against moderates like the Chartist bookseller, JB Humffray, about the strong action needed to achieve freedom from oppression. As a symbol of new world ideals, a white cross embellished with stars, on a blue background, had been stitched into a huge Southern Cross flag. It was flown at the centre of the gathering. Two motions were passed. The first came from a young Irishman, Peter Lalor. It called for the election of a new committee the following Sunday. He wanted more decisive action. Then, the Hanoverian Frederick Vern proposed that they all burn their licences and resist any consequent arrests. Nothing more than resistance was contemplated.

Rede, on hearing of this, (not doubting Hotham's approval) decided on a showdown. He would hunt for licences the next morning, hoping, he wrote, to isolate the belligerent and achieve "the support of the majority". It was a brutal approach to a sensitive situation. He also observed that if left alone the protest would subside, but at the expense of some loss of government authority. It appears that his authority was what mattered most to him. So he went ahead with the hunt.

This crucial hunt, on Thursday 30th November in the peaceful Gravel Pits, closest to the camp, was vigorously opposed. The police made no headway, Rede gabbled the riot act and summoned the military. Before they were forced to retreat, eight prisoners were taken. "At the risk of considerable slaughter", Rede claimed that he had "maintained the law". He was deluded. Animosity was universal. He had slapped them in the face. There was no "support of the majority". That he could have so seriously misjudged the situation beggars belief, unless, of course, his intention was to isolate the belligerent in order to deal with them.

News of the licence hunt brought an angry response from Eureka to support the Gravel Pits men. Spontaneously, they gathered a huge crowd which moved to the protest site at Bakery Hill, where the leadership passed to men who thought it futile to deal with a government dead set against justice and reform. The provocative licence hunt had brought a sea-change. Peter Lalor, an active and independent Irishman, but no democrat, mounted a stump, proclaimed "Liberty" and called for volunteers to form companies.

Significantly, Lalor led the protest force to his home territory, the Eureka diggings, well away from the camp. What was intended was not clear. Why, we must ask, did they build a makeshift stockade of carts and slabs, except to resist further licence hunts and to express their defiance? They behaved as the crest of the long wave of protest brought to breaking point. In its defensive character, the stockade was hardly an attempt, as Rede labelled it, to take over the colony. Tactically, it was suicidal. Revolutionaries would have planned an attack on the government camp. Despite efforts to gather arms and make futile pikes, they were ill-equipped and so disorganised that any concerted action was beyond them.

Rede's spies would have told him that they were no match for his professional force. In a junior officer council of war, expecting Hotham's support, and before a more dispassionate senior officer arrived, he decided to make a surprise attack on the two-day old stockade. At 4:00am on Sunday 3 December 1854, without warning or reading of the riot act, the assault began. It is hard to forgive that desecration of the Sabbath, so strictly observed in Victorian times. The Irish were expected at morning mass. All was over in twenty minutes. Against a handful of government casualties, thirty diggers were killed, half of them massacred, after the stockade fell, by malicious police and soldiers. They murdered wounded men, set fire to tents where families were sheltering and shot bystanders. It was an awful scene, made more poignant by the action of a grieving terrier, who would not be separated from the body of his master.

The political aftermath was dramatic. Defying their mayor and some Legislative Councillors, who tried to rally support for the government, Melbourne's citizens turned out in thousands to condemn the authorities. At Ballarat, only one man answered the call for special constables. Everyone was thankful when General Nickle arrived. The martial law he declared gave relief from Rede's arbitrary rule.

Everything turned sour for Hotham. His Royal Commission savaged the goldfields administration. Intransigent to the end, with the support of the Legislative Council, he refused, as advised by the Commission, to grant a general amnesty and defied it (at first) by re-ordering licence hunts. He did retreat on that, after the wholesale burning of licences at Bendigo and Castlemaine, but pressed ahead with charges of treason against the "rebels". The acquittal of thirteen defendants in February and March was received with great rejoicing, capped off on 27 March by the release of the damming Royal Commission report.

As a result, the miners' basic needs, denied for years, were met. An export duty on gold replaced the licence tax, and miners' rights costing £1 per year, secured claims. One warden replaced numerous gold commissioners and half the police were sacked. Eight goldfields members were added to the Legislative Council and local courts of mines, elected by the diggers, were created to regulate mining. Without Eureka, so much could not have been done in so short a time, for the emergency broke the grip of the pre-gold establishment. The vote, given at this time to holders of miners' rights, opened the way to manhood suffrage, which otherwise, considering the entrenched power of the Council in the constitution, might have come only after years of bitter struggle.

More than that, the way lay open for the talented and energetic gold migrants to develop Victoria. Their social democracy demolished barriers to self-improvement. In the tide of change opportunities were opened, that were unthinkable in the old world. Ballarat people thought of themselves as the best of Britons. Building on gold, but assisted by rich agricultural and forest resources, they created a mature city within their own lifetimes. You can read about it in Lucky City, and take in more detail from chapters 3 and 4 about the conditions and events that led to Eureka.