Women of Eureka

Background

Women of the Diggings

Australian women have been systematically excluded from many narratives of nation building and they have almost disappeared from some historical accounts. The historical record has been mostly silent on the presence of women at Eureka, preferring to focus on the event and deeds of notable men, and this has often been taken to indicate that women were absent. Thus the idea of women's invisibility at Eureka has been propagated.

It was not until Laurel Johnson wrote specifically about the Women of Eureka that they began to stir in our national memory.[1] But they were still not deemed as an important facet in the image of nation building nor did they dovetail with the masculinist image of the rough and tumble goldfields. Corfield, Wickham and Gervasoni included them and many of their interesting life stories in The Eureka Encyclopaedia in 2004.[2] Eureka Reminiscences included eyewitness accounts from two women. [3] In his history of Ballarat Lucky City Weston Bate acknowledged there were women and children on the goldfields and that items such as breast pumps and nipple shields were being sold.[4] Dorothy Wickham's PhD argued that women in Ballarat from 1851 to 1871 exercised agency and such gendered power relationships were often endorsed by both males and females.[5] In Women of the Diggings: Ballarat 1854 Wickham again explored and interpreted women's agency through work, political activity, family relations, birth, death and dying and argued that women on the goldfields, especially during the Eureka Affair, demonstrated a degree of agency, innovation and courage.[6] Clare Wright continues the tradition of writing women into the Eureka story in her The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka. [7]

Given the historical context and record, it is plausible and highly likely that women were active in the protests surrounding Eureka. Women traditionally were participants in similar social protests in Britain.[8] West and Blumberg have demonstrated clearly that women have traditionally been present in such social protests throughout history.[9] Reports claimed that around 10,000 people were present at each Monster Meeting of the Ballarat Reform League on 11 and 29 November 1854, these being 'quiet and orderly' occasions with flags and music 'adding to the effect of the affair'. [10] As Ballarat women comprised around 25 per cent of the local population in 1854 it is highly likely that they were among the crowd. Mrs Margaret Shann or Shand a striking looking woman said she was at the rallies as did Mrs Elizabeth Rowlands,[11]

While many women were undoubtedly aggrieved that neither they nor their husbands had a vote or representation in parliament, a more central grievance and a more immediate source of distress for families at Eureka was the high licence fee imposed by an authoritative officialdom and the ruthless manner in which it was collected. A high licence fee meant that women, children and men were suffering. It meant that money was spent and a tax levied from the family income before any money was earned. Stephen Cumming, a gold miner and witness at the 1855 Commission of Enquiry said that the present system was 'bad' where 'a man could be taken away from his family if he could not produce his licence'. [12]On 28 October 1854 one gold digger whose licence had only just expired, and who had no money, 'had to borrow half a bag of sugar ... for [his] wife and children'. [13]

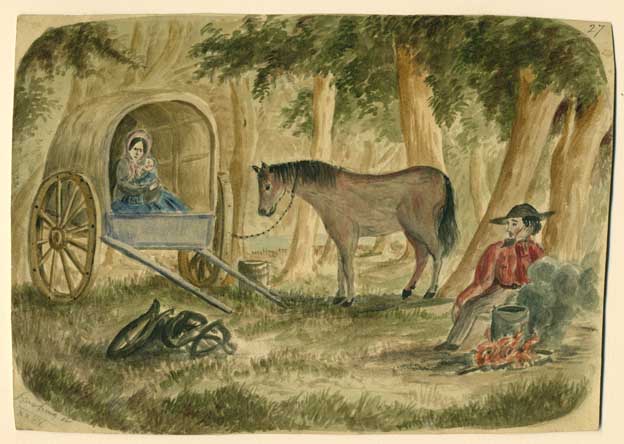

Oral and written testament places women and children not only at the scene of the fracas on 3 December 1854 at the Eureka Stockade on the Eureka Lead but also inside the Eureka Stockade.[14] Agnes Greig said she saw women and children evacuating Eureka and heading off towards Black Hill in the immediate moments before the battle. She witnessed the battle from a tent overlooking the Stockade. Patrick Curtain who had a store inside the Stockade 'tried to remove his family'. Lanty Costello, an ex convict, gave evidence that he left his tent with his family 'for a place of safety about a mile from the Stockade'. John Connelly also 'left with his family'.[15]

Other women remained inside the Stockade, supporting their husbands, brothers and fathers. The inventiveness of women in fighting showed both resistance and desperation. Bridget Hynes hid her husband's pike and pants to prevent his participation in the battle. She was reported to have run towards the gunfire at the Stockade and helped to protect the insurgents from the soldier's bayonets. Elizabeth Wilson who had a shop inside the Stockade was reported to have loaded her husband's gun. During the battle when he ran away she was in the Stockade area still and hid one of the insurgents under her petticoats, possibly saving him from death.

Dr Dorothy Wickham

Women in the Lazarus Diary

According to a handwritten account by 19 year old Samuel Lazarus on 05 December 1854 a woman and her infant was shot, but no evidence can be found in official death records. Lazarus wrote: Among the victims of last night's unpardonable recklessness were a woman and her infant - the same ball which murdered the mother (or that is the term for it) passed through the child as it lay sleeping in her arms. Another young woman had a miraculous escape. Hearing the reports of musketing and the dread whiz of bullets around her, she ran out of her tent to seek shelter - she had just got outside when a ball whistled through both sides of her bonnet.[16] The provenance of the Lazarus diary has been challenged and reportedly was written by Charles Evans. [17]

News

The Rights of Women

One of her rights was undoubtedly to be loved by her husband.

'Women was taken from near the man's heart to show that she was to be loved;

from under his arm to show that she was to be protected;

beneath the head to show that she was to be governed;

and above the feet to show that she was not to be trampled upon'.

As to her political rights, He considered they were strictly at home.

J.B. Humffray, The Star 19 August 1856[18]

Biographies

Elizabeth Abbott; Susan Blight; Alice Eureka Boyce; Eliza Buckland; Amy Cail; Mrs L.F. Cavanagh; Bridget Callinan, Mary Chamberlin; Catherine Daw; Agnes Greig; Sarah Hanmer; Elizabeth Amies; Margaret Baker; Catherine Bentley; Mary Blyth; Eliza Boyce; Eliza Buckland; Amy Cail; Bridget Callinan; Martha Clendinning; Margaret Clendinning; Ann Crowley; Mary Davis; Ann Diamond; Catherine Donnelly; Elizabeth Doyle; Charlotte Drew; Ann Duke; Alicia Dunne; Phoebe Emmerson; Adeliza Faulds; Mary Faulds; Eliza Forster; Elizabeth Freeman; Agnes Frank; Penelope Gleeson; Mary Goldsmith; Margaret Guthrie; Agnes Greig; Jane Hanson; Anna Harrington; Anastasia Hayes; Jane Hotham; Mary Ann Humphris; Bridget Hynes; Ann Johnson; Margaret Kinnane; Sophie LaTrobe; Sarah Lloyd; Sophia Marks; Susannah Masfield; Catherine McLaren; Sarah Morgan; Lydia Mullett; Ann Perkins; Eliza Perrin; Bridget Powell; Nancy Quinane; Nancy Ryan; Elizabeth Rowlands; Phoebe Scobie; Mary Hannah Searl; Clara Seekamp; Bridget Shanahan; Margaret Shann; Catherine Smith; Emma Smith; Patience Wearne; Elizabeth Wilson; Anastasia Withers; Ellen Young

See Also

Dorothy Wickham, Women in 'Ballarat' 1851-1871: A Case Study in Agency, PhD. School of Behavioural and Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Ballarat, March 2008.

Dorothy Wickham, Blood, Sweat and Tears: Women of Eureka in Journal of Australian Colonial History, 10, No, 1, 2008, pp. 99-115.

Dorothy Wickham, Women of the Diggings: Ballarat 1854, BHSPublishing, 2009.

http://www.eurekapedia.org/Blood,_Sweat_and_Tears:_Women_at_Eureka

Clare Wright, The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka, Text Publishing, 2013.

Dorothy Wickham and Clare Gervasoni, ABC National Broadcast, 7 January 2013, Genealogy, Interview with Simon.

Dorothy Wickham, Not just a Pretty Face: Women on the Goldfields, in Pay Dirt: Ballarat & Other Gold Towns, BHSPublishing, 2019, pp. 25-36.

References

- ↑ Laurel Johnson, Women of Eureka, Historic Montrose Cottage and Eureka Museum, 1995

- ↑ Corfield, Justin, et al, The Eureka Encyclopeadia, Ballarat Heritage Services, 2004.

- ↑ Eureka Reminiscences, Ballarat Heritage Services, 1998.

- ↑ Weston Bate, The Lucky City: A History of Ballarat from 1851 to 1901, Melbourne University Press, 1978

- ↑ Dorothy Wickham. Women in 'Ballarat' 1851-1871: A Case Study in Agency, Volume 2, PhD, School of Behavioural and Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Ballarat, March 2008.

- ↑ Dorothy Wickham, Women of the Diggings: Ballarat 1854, Ballarat Heritage Services, 2009

- ↑ Clare Wright, The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka, Text Publishing, 2013

- ↑ Dorothy Wickham. Women in 'Ballarat' 1851-1871: A Case Study in Agency, Volume 2, PhD, School of Behavioural and Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Ballarat, March 2008.

- ↑ Guida West and Rhoda Lois Blumberg, Introduction, in Women and Social Protest, ed. Guida West and Rhoda Lois Blumberg, New York, Oxford University Press, 1990.

- ↑ The Illustrated London News, 25 November 1854, p. 587.

- ↑ Dorothy Wickham, Women of the Diggings: Ballarat 1854, Ballarat Heritage Services, 2009

- ↑ Dorothy Wickham. Women in 'Ballarat' 1851-1871: A Case Study in Agency, Volume 2, PhD, School of Behavioural and Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Ballarat, March 2008.

- ↑ Dorothy Wickham. Women in 'Ballarat' 1851-1871: A Case Study in Agency, Volume 2, PhD, School of Behavioural and Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Ballarat, March 2008.

- ↑ Dorothy Wickham. Women in 'Ballarat' 1851-1871: A Case Study in Agency, Volume 2, PhD, School of Behavioural and Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Ballarat, March 2008.

- ↑ Dorothy Wickham. Women in 'Ballarat' 1851-1871: A Case Study in Agency, Volume 2, PhD, School of Behavioural and Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Ballarat, March 2008.

- ↑ Gripping Diary Captures Moment in Australian History IN The Age, 02 September 2006.

- ↑ Clare Wright, Forgotten Rebels of Eureka, Text Publishing, 2013

- ↑ John Basson Humffray, The Star 19 August 1856

--Dottigee16 (talk) 15:37, 25 November 2013 (EST)

Please ensure correct attribution as outlined at - http://www.eurekapedia.org/index.php?title=Special:CiteThisPage&page=Women_of_Eureka&id=18387